Leili Florence Besharat

Nepal

The soul of a journey

is liberty,

perfect liberty,

to think, feel,

do just as one pleases.

--William Hazlitt

...though not a true man

of action, he found motion

a useful state in which to deal

with his feelings.

--Thomas Berger

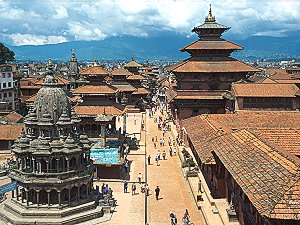

Kathmandu

I got lost walking down Freak Street and wandered into a small alley only because a stretch of green silk was winding in a spiral in the breeze, held by a clothespin, but its tip struggling towards me nevertheless. I was so engrossed in the struggle of the silk that I didn't notice until a few moments later that a boy was sitting on his scooter by the gutter. From close up you could see the gutterwash staining the tip of his foot closest to his girl, who he was courting. He was holding her waist loosely with one hand. As I got closer, I could see he donned a mask, a rubber ghoul. The kind a kid wears on Halloween. It was a stark, blanched white, with black holes for eyes and a parched mouth. A phantasm. The girl giggled and pushed him away but I could see she was pleased by the way her eyes ran around his face. The juxtaposition was odd: gutter, green silk, huge head, boy's body, giggling girl.

I walked away, feeling as if I were watching something private, and looked back only when I was about to turn the corner. From far away, he looked like a cloud eating a girl. That night, I dreamt of the reverse: cloud-eating girls, engrossing their companions in idle chatter, enveloping them in mist. Reclining Vishnu, sleeping on the cosmic ocean, surveying the divine consumption from his dormant perch. Three incarnations short of waking.

In Nepal, they place stones all over their roofs to keep them from flying away. The roofs soothe me. Every time I see a stone-staid roof, it makes me feel as if my head is more firmly clamped on my head, the stones serving me too in all their capacities for containment.

Coming from living in Thailand, I invariably notice about the Nepalese the differences against the backdrop of Thai culture. I notice most the thickness of the hair, the intensity of the eyes, the particular rhythm of the music. The dancing, with every dimpled gesture crammed full of meaning. One night, my friend and I enter a men's club in Pokkhara, the women dancing to Urdu love songs stabbed with techno beats. I'd never seen such an innocent yet erotic mileau: there was no shedding of clothes, nothing lascivious even implied, and yet the sensuality of the dancers was undeniable. I didn't understand the words to the songs, but the movement of the women against the grain of the words moved me. One girl in particular. She came onto the tiny stage soaking wet, as if she'd been caught in the rain. Dense with glamour a little despite, a little because of the cheap Christmas lights, the large sign that warned the audience "NO DANCING". The stage was so simple that it looked almost fake. So miniature that, when the woman came on to dance, she appeared larger-than-life, intricate, complicated. Her eyes were half-mast, stinging from the dust of some imaginary dune, and her gaze rested firmly on my friend and I, the only foreign women -- the only women -- in the room. It was a gamey gaze, one that tried to decimate with some lament. She reminded me of the Buddha in the Wat Simuang cloister in Vientienne, the one in the "Calling for Rain" pose. The trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Siva all wrapped up in one Christmas-lit girl.

We met a boy in Kathmandu named Deepesh, a perfect, inviolate boy of sixteen. He had dark, deep-set eyes like open apertures, eyes that looked at you with intent, as if he were trying to make merit in every small nod, blink and gesture. His presence with us for twelve hours one day was close to evanescence. They all call us sister here, but coming from his mouth it sounded different.

We had not met only good boys in Nepal. Jack Merridew's progeny were out there: street kids who were attracted to our na´ve, open faces, the lanky way we walked. They reminded me of the mythical denizens of Phousi Hill in Luang Phabang, the powerful naga she harbored in her bowels. Stung sea snakes, now intent on doing the stinging. The first night we had met a young junkie, all dead eyes and track marks, so effeminate that I did not know what sex he was until I located his Adam's Apple. Lantern-jawed sea snake boy who spit out "I'm from the Land of Peace and Eternal Love" at passersby, he snowed us for more than we cared to admit, conniving us down a dark alley. The milk powder and biscuits we bought him, we realized later, were a shabby front for drugs. In bed later that night, the color rose high in my cheeks like dark blooms as I realized how he had manipulated us in dozens of little ways, more cleverly in thirty seconds than any used car dealer or fake guru could ever manage. The boy had talent. "There are people here," he said so solemnly it sounded faintly ridiculous, "who would kill your smile from you. Just. Kill. It. Watch out for those."

Deepesh was not like this. He held a vulnerability that was remarkable given his life. He was fond of aphorisms like "life is a for-living thing, sister." He asked funny questions with no answers. "Do you know that commercial 'so comfortable it makes you forget', sister? Forget what?"

He came upon us one morning in the velvet clutch of the temples, making idle conversation. We were dismissive of him, having been resolved to close ourselves off from that point on to young men approaching us. He looked remarkably like the young junkie the evening before, except he was alive in all the places the other was extinguished. Because of this, I couldn't help but think of Cain and Abel, of the two extremes of human potential, first tempting us and then calling us fools when we drew to close (which is really what any lesson involves). Deepesh had such an impact on our good graces, and it was hard to fathom exactly why. Here was another kind of manipulation, but one that was mutual and made of pure light. We brought him to a restaurant and, as we had seen him do before, he excused himself to wash up -- coming back drenched, having soaked his whole head in the water. As he sat down to eat, his lower lip quivered a little and his hand shook. He had the malnourished grace of someone used to waiting a very long time. Expecting nothing. Not knowing quite what to do when something out of the ordinary presented itself. He was not used to eating with tools and, even when we started eating with gusto with our right hands, as is the custom with dahl, he insisted on eating with a fork. When he was finished, he leaned over conspiratorially. "Sisters, I promise you, if I eat this dahl with my hand, it takes thirty seconds flat, no more. I promise you this." His high plains for cheekbones were ruddy with the emotion of the statement. "Are you happy, sisters?" he asked, grazing our wrists with his fingers. As we were about to leave Kathmandu, saying our goodbyes, he gazed at me like a lamb lost in the fold. "Sister, what next?" Another plea for an answer I hadn't a clue how to mouth.

The backpackers in Nepal we sometimes find odd, or maybe it is us. When we sit down to eat one night, a man from an indefinable country stares at us as we giggle over a secret joke. My friend and I have been traveling together for awhile, and our conversations weave around the same topics with new twists, randomly overlapping in a way that must be nonsensical for anyone listening. We've developed a shorthand, and she soothes me when I'm sick by reading the Indian matrimonial ads, with their obscene specificity, their namedropping, their overuse of the words "decent" and "respectable", as if the meanings were a name brand you can pick off the shelf. We talk quietly but animatedly that night about various subjects. The meaning behind the words "counterbalances" and "counterclockwise." How our fathers tried to get us to understand time so patiently and how it took forever to grasp. How you take pictures of people because you want to take a little piece of their soul with you and that's precisely why they don't like it. The over-use of the word "full-on." The stillness of being reborn through motion. The modern miracle of contact lenses and how we would be cripples in earlier times without them. How we like to be as geographically far from our ex-boyfriends as possible, at least one country away if we had our druthers. How Hotel Blue Heaven is the most evocative name for a dwelling ever. We talk of how terrible we felt over mistakenly moving against the traffic of a prayer wheel our first day in Nepal. We discuss the yellow-scarf-strangling Thugees of yesteryear, with their sugar sacrifices, which we still only have a vague, toddler's grasp of -- imagining one side proclaiming "Don't hurt the sugar!" while the other chants "Spill it! Spill it!" barbarically. We ponder the practice of night hunting we had heard of in Bhutan, married men looking for chum through darkened glass windows. We find it both frightening and amusing, and speculate over possible "Room Service with Night Hunter Option" as a pull for single tourists ("Boys with good bone structure need only apply") I tell her about the little Newari girls betrothed to a tree, and how you could always compare your man unfavourably to the tree ("well, my tree would never behave like that").

The backpacker listens to our rambling and stops us mid-discussion while we're trying to figure out what tree we would choose as a first husband: a rambling oak, an exotic twisted baobab, a stunted pine with potential...He uses loud, muscular words to take charge of the situation, beginning a monologue about his experiences in Korea. The guiding impression he came away with was that the underwear tags all said "Made in Korea" but it was all really manufactured surreptiously in the United States. It seems like a particularly obscure form of paranoia, nestled over the military industrial complex. Manifested in Korean wife beaters and tighty whities.

Monks with faces like half-moons. Bent in repose. So contained. The thing about a lot of us is that we like our longing. We're accustomed to it. We have no wish to get rid of it, even if we admire those who have. If we tried to rid ourselves of longing, we'd only long for it the more, pining for the longing itself with more fervor than any of the objects it ever held.

A child tip-toes on an old torpedo casing. Practicing for the high-beam. Squinting at me like a six-shooter, lodging fake bullets at my chest. When I fail to please him, he lets out a sound like a train-whistle. Like an approaching tornado.

Sonauli

Border towns are odd. They're neither here nor there. They cross that thin, disturbing line that sense of place distributes to us: "You are Here. Here are the rules for Here. Here is how to behave Here, what to eat Here," rules that I notice travelers like to follow to approximate the nest-egg of home they've left, of knowing What to Do and When. Border towns have an identity crisis and I try to avoid them because, where they are supposed to imply boundaries, they're fuzzy, boundary-less messes.

The way a bus or truck driver decorates his vehicle says a lot about the person. In Prague, naked girls and a warped aesthete's chintz. In Laos, plastic grapes and Buddha. In Nepal, Hindu goddesses and a riot of color, each truck a private celebration. All of them, mini-shrines of comfort in a comfortless stretch of road, declaring personal boundaries, separating them gently from their passengers. Everyone longs for autonomy in their realm, whether rickshaw driver, taxidermist, exotic dancer or prime minister. Everyone wants to be king of her geography.

My friend tries to pet a white dog she sees on the street, who ambles away. Moments later, a child comes with dog in tow, tugging it her way. He takes her hand and places it firmly on the dog, moving it back and forth in a stroking motion. I watch all this from a distance. The effort this little boy makes in pleasing a stranger is remarkable to catch mid-gesture.

Climbing up Sarinkot, all the children ask us for biscuits. One little boy strikes me, a dwarf still in his growing years. He asks for nothing, but I hand him a half-melted Mars bar as I'm descending. He whispers "Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes", five yes'es, crammed together like one word. As if I might take it away if he doesn't produce the right amount of them. He clutches the candy to his tummy and immediately rips it open to share with his sister.

The touts in Nepal are like touts everywhere, whether in Vietnam, Laos or the few that are phasing out in Thailand. Impossibly black with sun, weathered maps for faces, and soles of the feet broken, cracked, manipulated, after years of cycling, to take on the ridges and creases of the pedals. Craters of dead skin and calluses. I love these feet. Everytime I sit in a rickshaw or cyclo, I stare at the soles of the man struggling before me ever-so-slowly and want to tend to them like Jesus.

I fall in love with the way I hear language mutated -- the way mediocre communication of basic information is turned unwittingly into little haikus, little crack-ups with provocative punch-lines. In Nepal, as in any other country, the English language is funneled through the body of the country and picks up her own manipulations and mannerisms. Just as I thought I was saying "I am teacher" around Nepal but was really saying "I am tender" (because that is what a travel guide had thought I wanted to say to everyone), so the language sheds itself of literal meaning and takes on odd, personal nuances. "The lift is closed for repair" becomes "life is closed for repair". "Please keep clean" becomes the sweetly insistent "please keep cleaning". Instead of "Wishing you a nice stay!", we have "Wish you had a nice stay!", which is another wish entirely. Tense changes everything. Absolutely everything.

©2003 by Leili Florence Besharat