|

My father was a soldier and a blacksmith. and the sacrifices he made were for his God, his country, and for me. Now, some thirty Octobers from adolescence, from the invincibility and ignorance of youth, I spend the better part of my day thinking of him and wishing I could have, would have, done more to help him through the tough times, or at least, not to have done so many things to make the tough times tougher. But I didn’t, and I’m sorry. It has been said that memories travel best with the wind, and I believe they do. For there is a particularly fond memory of mine that moves with the cool easterly breezes that howl through the valleys of the Appalachian Mountains, breezes that move swiftly along its rivers and through the red, yellow, and brown leaves of its forests. It’s this mountain wind that picks up and carries with it the familiar aged scent of elm and hickory and the sweetness of sassafras. But perhaps for me, the most neurologically stimulating aroma is that of horse manure. It is also this wind, and this scent, that always seeks me out -- when I’m seated on an outcrop of rocks at the edge of a gorge, when I’m hiking the towering ridges of the canyons or the shady foothills, or when my feet are submerged in the swiftness of a stream that cuts through it all. And when it does, when it overcomes me, it takes me back, back to a farm, back to a barn, back to a hay-covered floor where I waited for my father. And it was here, as a small child, that I prepared to assume the duties of a "horse-fly watcher." From the recesses of my mind and through the damp early morning fog and the doors of that barn came the man whom I’ve forever since been trying to become. He wore old cowboy boots, jeans that were faded and ripped, and an old T-shirt with a pack of Pall Mall cigarettes protruding from the breast pocket. If you asked him why he dressed the way he did, as I never thought to do, he’d tell you he liked what he wore to be broken in or that perhaps next payday he’d buy something new for himself. But what he wouldn’t tell you, not in a million years, was that he’d spent what little money he had on me. He held a rope in one hand and an old coffee can of molasses grain in the other. Obediently following behind him, attached to the rope but not pulled by it, walked a shiny black horse. Now, with the help of the wind, I remember that he often told me the key to catching a horse was not to chase him (since he with the most legs would surely always win) but rather to convince him. Convince him to come with you. Convince him you’d take care of him, protect him; that you’d let nothing happen to him while he was with you. He told me this as if he somehow knew I’d be a teacher one day. Now, as I struggle to get through to the at-risk students seated in my class, I feel the wind and hear his words, and I continue to become just a little more like him. Nailing metal shoes to the bottom of horse hoofs was sort of a family affair. It had really little to do with nailing metal shoes to the bottom of horse hoofs. The work was hard and the pay was little, but now as I look back, I realize that while riding around in that old pickup, going from farm to farm, I was introduced to the West Virginia of my dreams, vast, tall, and green. It was also here, next to my father, that I met many of her most precious people, and especially now, I know that I spent many priceless hours with the best man I have ever known. I held the leather reins in my hands while my father fetched tools from the back of a rusty, 1965 Ford pick-up truck, coated with dust from the back roads that snaked between, around, and over some of the steepest hills in the state. Meanwhile, the horse curveted and capered, and its heavy hooves thumped against the barn floor. It immediately calmed when my father returned and ran his hand across its smooth, solid neck, up into its coarse main. The horse’s large black eyes reflected the rounded fish-eye image of an honest, gentle face, the face of a man who’d experienced much hardship and despair. It was that same hand, that scarred, callused hand, that bore the only surviving token of broken marriage vows, that also calmed me, that had made me feel safe so many times before. I was left to assume, as did anyone who ever shook his hand, that they were the hands of a soldier or at least the hands of a man who had had it rough. I can remember, only faintly though, when the wind is not so strong, a faded bumper sticker on the back of that old truck that read, "Proud to be an American." This now strikes me as ironic, ironic that a man who was sent to fight an enemy who was not his enemy at all, and who was seriously wounded by that enemy, and who returned only to be spat upon by the people he was protecting and alienated by the very government that sent him, would stick a bumper sticker on his truck declaring his allegiance to those very things. Maybe I’m still too young to understand this. My father learned his craft from an old horse trader named Burt Brown. Burt had looked after my father when the West Virginia coal mines gave my grandpa a black lung, a pine box, and a pension that was not enough to feed his six children. With my grandfather buried in an unmarked grave behind their company house, my father was left to take care of his mother and sisters. So, at the age of fifteen, my father became a blacksmith; then at the age of seventeen, he became a soldier; and finally, at the age of twenty, he became a cripple. In spite of his disabilities, I was astonished by my father’s unparalleled strength as he gripped the tuft of hair on the back of the horse’s hoof and by the way he lifted it, with the beast’s cooperation, to his thigh on which it was supported. The prosthetic replacement of the leg amputated in a field hospital in South Vietnam shook a little, but never—as he never—gave way. And while the war made him technically disabled, his years of blacksmithing gave him a crushing grip and the muscular build of a floor safe. Yet, his manner remained open and gentle. Since I was small and could help little with the manual labor of horse-shoeing, my father assigned me the august responsibility of watching for horseflies. It may not sound like much, but I assure you, it was quite an important job. If it were not for me, horseflies could come and go as they pleased, free to bite the horse my father was working on. And if the insects were permitted to land and subsequently bite the horse, my father might be seriously injured, or even killed by the thousand-pound bucking beast. So, like my father, I took my duty quite seriously. Still today, I can spot one of the large, robust bloodsuckers anywhere, any time. I had studied them, learned their ways. As if he knew I’d one day be a soldier, my father once told me all good soldiers know their enemy. And like a good soldier, I knew mine. It had short antennas, a broad head, and a flattened body and was brilliantly colored. I also realized that, for the same reason I couldn’t hold the heavy horse hoofs, pound nails into them, or bend the metal shoes, I couldn’t do much to prevent the other bloodsuckers from hurting my father: the bill collectors who sent notice after notice, the foreman who fired him because he couldn’t move as fast as the other workers, the wife who left him to deal with the post-traumatic stress disorder on his own, and the government who gave him a Purple Heart and thirty percent disability for the leg they blew off—money that did little to help him raise me by himself. So, it was there at my post that I stood watch, searching diligently for the elusive insect as my father worked. Across its back, under its large round belly, then over its flanks -- anywhere the horse’s whisking tail could not reach. Though not often, I occasionally watched my father work. While his sacrifices meant little to me then, they now mean everything. My father always began his work with a friendly pat on the horse’s rump and a, "Hello, old friend." Then, one at a time, like a surgeon, he chose a tool and fixed the horse’s feet. While holding the hoof with the bottom facing up, he removed the old shoe with a device resembling a pair of pliers and then, using a knife with a narrow-blade and a severely curved end, he cleaned the bottom of the hoof. "If the hoof gets too dry and hard, it cracks; but if it's too pliable, it bruises easily, leading to abscesses or infections," my father told me, as if he knew I’d one day care for others. Then, after cutting away the callus-like growth from the underside of the hoof, he used nippers to trim a quarter-inch-thick semi circle from the bottom of the hoof. Next came the rasping of the hoof bottom into a flat surface, and it was here that my father had to consider the horse’s biomechanics and individual hoof shape. Although he possessed only a ninth grade education, he did it perfectly every time, like a scientist or engineer. Next, he chose a long file he referred to as a "rasp" and filed down the hoof until it was smooth, clean, and evenly rounded. Between his teeth and sticking out from his thick red mustache, he held eight flat one-and-a-half-inch nails, one for each of the holes in the horseshoe. He held them there for easy access because both of his hands were full—a hammer in one and a horseshoe in the other. Then, he put shoe to hoof, attaching it with a nail on each side, careful to ensure that the nails came through the hoof. Once the shoe was in place, he hammered in the others and cut and filed each of them. Finally, he filed the leading edge of the hoof so it was flush with the horseshoe. If my memory serves me correctly, or if the wind is strong enough, I believe from start to finish the process took seven or eight minutes per hoof. "Does the horse feel anything?" I asked my father. I asked the same question every time I watched him remove a nail from his mouth and hammer it into the horse’s hoof. "No. The hoof's like your fingernail," he replied with a full, comfortable smile. And I can remember, even without the wind, with great fondness and admiration, a saying my father recited as he worked. "For want of a nail, the shoe was lost. For want of a shoe, the horse was lost. And for want of a horse, the rider was lost." He went on to advise me that "If a horse is shod improperly, he can break a leg, cause a spill, make riders go down. People can break necks and die." This, too, he told me as if he knew I’d grow up to help people. "Dad!" I shouted in a fit of anxiousness. "Yeah, Son?" "I see one." "Alright," my father replied calmly. He released the horse’s hoof and let it clomp back down on the barn floor, and stepped back. "Go ahead, boy." Finally, it was my turn, my turn to help him. There was no way I was going to allow my father to suffer any more pain. I would not allow him to shed one more tear. I would take care of him as he had taken care of me for eight years. So, with my Dad proudly watching, I snuck quietly up beside the horse like a soldier, my reflection captured in the large black eyes that searched for the source of the silence. Then, with my small hand flattened, I carefully brought it up behind the fly, cautious not to startle it, and counted to myself—one, two, and on three, the horse let out a loud snicker and bucked a little. When I removed my hand, I watched as the fly fell to the ground and buzzed helplessly in the sawdust and hay. I crunched it under my foot, the proud foot of a "horse-fly watcher."

©2002 by Emmitt Maxwell Furner, II

|

| Home | Contributors | Past Issues | The Ten | Links | Guidelines | About Us |

|

|

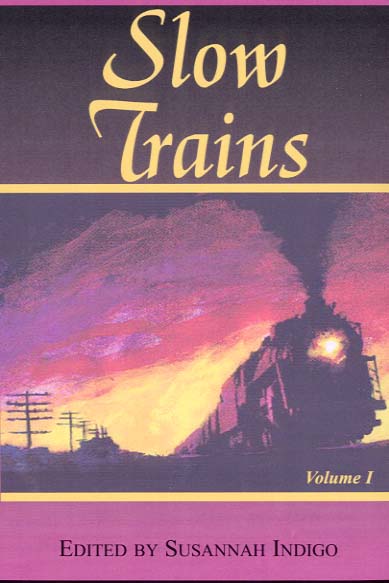

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print

|