|

Trading Ethics

by Jeff Beresford-Howe

Baseball has hit the quarter poll this year with the usual suspects firmly in place -- the Yankees, Schilling and Johnson, Bonds and Sosa, A-Rod, declining attendance at the boutique ball parks -- but a few surprises, too.

There's the descent to merely human status of Red Sox ace nonpareil Pedro Martinez. Spirited runs by the Anaheim Angels and the Cincinnati Reds (who did almost all of theirs without the injured and ineffective Ken Griffey, Jr.) seem likely to continue throughout the summer. The good play of the doomed Montreal Expos defies "contraction" rumors, on the field, at least. Then there's Montreal's contraction partner in Minneapolis, where the Minnesota Twins are winning on and off the field and may have preserved their place in the game while revealing baseball's newest superstar, Torii Hunter. There's also the stirring pitching of Kazuhisa Ishii in Los Angeles and the continued spectacular success, despite injuries and off years from key players, of the Seattle Mariners. Is there any serious doubt now that Ichiro Suzuki is the most valuable player in the game?

But the biggest surprise is that the top stories in baseball are taking place off the field. They involve ethics.

No one talks much about ethics in baseball. The game itself encourages this lack of dialogue. Transcendent talent is a scarce commodity. If you can hit .320 or win 20 games, it doesn't matter if you beat your wife, espouse bigotry in the name of Jesus, lie about the source of an injury in order to rip off millions of dollars or try to hurt other players with thrown balls and bats. On the other hand, if you're hitting .220 or you're a pitcher who can't make it out of the fifth inning, St. Peter may be falling all over himself to praise your good works, but you're going to find yourself riding a bus in West Texas, wondering why Midland exists.

There's a certain rightness to this: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and David Justice, to name three players who've had "character issues," make the game better to watch. It doesn't matter what they've established about their character. You want Bonds to continue his assault on Henry Aaron's home run record, or Clemens on the mound in a big game, or Justice teaching younger players how to handle the playoffs.

The ethical trade you're making -- the public, often sublime nature of these players in a ballgame vs. their distasteful or even criminal private behavior -- seems reasonable. Their off-field actions may hurt their friends, family and lovers, but rarely anyone beyond that circle.

The trade seems foolish, though, when we're talking about people connected to baseball who don't play, who don't give us any particular pleasure and whose actions can have much more serious real-world consequences.

The man who has most dominated headlines so far this year is a cramped, deceitful man who is at all times in desperate need of a decent haircut, i.e., Bud Selig, the commissioner of baseball.

What's the famous line about politicians? "How do you tell when he's lying?"

"His lips are moving."

Selig's a lot like that. This year, he has:

- repeatedly lied about baseball's finances, including in sworn testimony before Congress;

- engaged in a long-running conflict-of-interest over his continued control of the Milwaukee Brewers, one of baseball's two or three most pathetic franchises. This is a team which has, since Selig solidified control of the commissioner's office, been awarded next month's All-Star game, been allowed to become the first team ever to switch leagues and been labeled as "untouchable" in the contraction wars despite being a basket case on the field and at the gate since 1983;

- continued his long-running attempt to crush the player's union in an attempt to reap billions of dollars for his fellow owners;

- traveled across the country, blackmailing financially strapped cities into building new stadiums; and

- made elimination of two teams his number one financial priority, despite clear evidence that the industry as a whole is profitable.

None of this is surprising to anyone paying attention in the Bay Area. This is the same Selig who two years ago conspired with fellow owners to violate the spirit and intent of the late, great Walter Haas.

Haas, facing cancer and intense estate taxes, sold the Oakland A's to a couple of real estate sharpies in the Bay Area. Haas sold the A's cheap, with the understanding that the new owners would keep the team in Oakland and invest in it. Just in case -- poor Walter must have been delusional, not trusting real estate developers! -- he added a provision that if the new owners wanted to move the team out of Oakland, they first had to offer it instead at a discount to local investors who would keep the team in town.

It came to pass that these real estate guys did want to move the team. As per their deal with Haas, they offered the team to local investors who were willing to give them $125 million for it. (A substantial profit for the real estate guys, by the way.) Everything was ready to go when major league baseball owners, at Selig's direction and taking advantage of baseball's anti-trust exemption, voted not to accept the new owners. The real estate developers are now legally off the hook and can now do whatever they want with the A's. Haas's will, I don't think it's too harsh to say, was raped.

As much as talk of contraction and labor disputes and money and Selig's machinations in all these areas have been Topic A in baseball, the resolution, or lack of one, of another ethical issue may turn out to be Selig's legacy.

The use of steroids, human growth hormones and god knows what else in baseball has been an open secret for years. Mark McGwire confessed to using growth hormones, and I don't know of one person in or around baseball who thinks he didn't use steroids, too.

The issue finally burst completely into the open when Jose Canseco -- "And a child shall lead them"? -- confessed to using steroids and said he's going to blow the lid off the whole issue when his autobiography comes out. Ken Caminiti followed that with a confession of his own use of steroids in "Sports Illustrated." Both are one-time league MVPs.

Players with dramatic leaps in musculature and home run totals -- Bret Boone, Luis Gonzalez and Brady Anderson come to mind -- are almost certainly on one kind of juice or another. Sammy Sosa? Ruben Sierra? Clemens? Jason Isringhausen? Gabe Kapler? You look at before-and-after pics of them, say from their first year in the majors and now -- and it suggests that they had some sort of help.

These guys are hardly unique. You can find several on every team. Canseco says about 85% of players in major league baseball use steroids; Caminiti said the number was about half.

(It should be noted that Caminiti later retracted his claim, saying "my remarks were taken out of context." It should also be noted, though, that the context in which Caminiti operates includes his probation for cocaine posession. Use of steroids violates that probation.)

Curt Schilling, the Arizona pitcher who has emerged since Sept. 11 as a man of conscience and eloquence, puts the number of users at half, and he goes as far as to add, "the home run records are tainted."

Which brings up Barry Bonds, the man who actually holds the home run record. He told Bob Costas he doesn't use steroids, but Costas didn't ask him whether he uses other products, or, as Skip Bayless pointed out in the San Jose Mercury News, how Bonds achieved the freakishly unusual feat of putting on 30 pounds of muscle after the age of 30.

(For a man who says he's doing nothing wrong, Bonds has also made some very threatening, personal remarks to the San Francisco Chronicle about Canseco's desire to "name names.")

In any case, there are other indications that the number of users is very high.

Dave Nightengale, the fine USA Today reporter, quotes Bob Watson, the former player and now a major league baseball factotum, as saying that about a third of the minor leaguers selected as potential US representatives at the 2000 Olympics tested positive for performance enhancing substances and had to be left off the team. (The Olympics, like FIFA and most other international sports agencies, bans such substances and is constantly trying to find new ways to detect them.) This is especially disturbing because the players knew they were going to be tested.

This number is confirmed, Nightengale notes, by the San Diego Padres, who test their minor league players -- by terms of the major league labor agreement, they can't test their major leaguers -- and found a third of them using performance enhancing substances.

The major league percentage might be even higher. The players aren't tested at all and therefore can't get caught. (They are randomly tested before the season for recreational drugs. Testing for performance enhancing substances would be a simple matter. As long as the results aren't used against any particular player, it's probably not even in conflict with the player's agreement. And may even have already happened. Every time major league baseball, i.e., Selig, says he doesn't know the extent of the problem, consider that.)

There is a sense among players who talk about it that they are now in a ruinous "arms race," in which they consider the problem so prevalent that they can't compete and keep their very high-paying jobs without doing it themselves.

It's hard to blame them if that's true, but it's still cheating. It severs the link between fans and players -- one of baseball's charms has always been that regular guys could excel at it -- and between current and past players. It encourages players to engage in a form of drug abuse that clearly has short term benefits but is brutally unhealthy over the long term. It will destroy bodies and shorten lives. It means we're going to spend a fair part of the 2010's and 2020's watching current steroid users deteriorate in horrible and painful ways while whoever is then running baseball says, "In hindsight, they should have stopped it, but how could they have known?"

(The best writing I've ever seen on the subject of the body's deterioration after prolonged steroid use is a piece by Paul Solotaroff, which appeared in the Village Voice in 1991 and is included in the Best American Sportswriting of the Century, David Halberstam, editor.)

Testing isn't necessarily an easy answer -- the NFL has testing, for god's sake; do those guys look normal to you? -- and the Olympics have had a fitful time with their testing program.

Still, if major league baseball doesn't do it, it may get done for them. State Senator Don Perata, a power in the California legislature, has introduced a bill to require any team that plays games in California, home or road, to have a steroid testing program in place.

However, it's not impossible that Perata, who could make Machiavelli blush, and who both represents the district in which the Oakland A's reside and wants to be Mayor of Oakland, may have introduced the bill as leverage with Selig to avoid the possibility of the A's being contracted.

©2002 by Jeff Beresford-Howe

Jeff Beresford-Howe is a writer living in Oakland. Read more of his work in Bob Dylan: An Appreciation of How He is Now and Standing Up Against the Yankees.

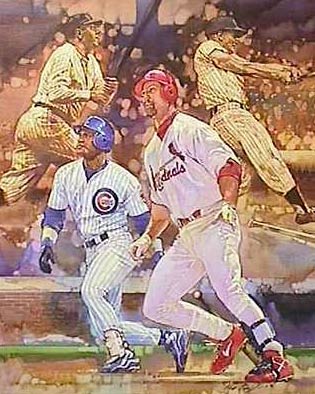

Art print by Ken Call,

Homerun Legends.

|

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print