.

Eat, Eat, Eat

by Kate Baldus

Mention Bangladesh to most Americans and they think one of three things -- floods; the poorest country in the world; or,

diarrhea. I, however, thought it sounded like a great place to spend a year, and aggressively pursued an opportunity to teach

in a private university in the capital, Dhaka. I tend to travel to places that others prefer to learn about through

documentaries. To me this was a country so far from my home in the United States that it could only widen my perspective on life and

the world; my friends and family, however, were not so sure it was the best idea.

The first person I told about my new job in Bangladesh said, “You can’t drink the water there. You’ll get...” then did not finish the

sentence. The second said, “You can only eat vegetables that are peeled in that kind of place, otherwise you will get

terrible diarrhea.” Emphasis on the terrible, said with their voice going up. The third person’s response was, “What kind

of food do they eat there? Will it give you?...” Then a breath of silence. The people I knew only thought of one thing when

they heard I was going to Bangladesh -- diarrhea. Diarrhea. Diarrhea. Diarrhea. Diarrhea became the refrain, and soon

everyone was worried about my intestines and body weight. And because I am a slim woman who has worn the same size

jeans for over fifteen years, my close ones became convinced that Bangladesh would be the end of me.

Having suffered from diarrhea and bacterial disease in other parts of the world, at first I thought my friends were over-reacting. In Bangladesh one might get diarrhea as easily as we get colds in America, but I was confident that I would get

over these stomach troubles as easily as I did the sniffles and a fever. Besides, I was buying pounds of stomach medicine to

deal with all the symptoms. But the closer I came to my date of departure, the louder the comments grew. The worry for my

bowels transformed into worry about my health, my well being, and the future of my not yet born children; soon, buying

Pepto Bismol, Imodium, and ciprofloxin was not enough to allay the simmering fears, until my friend Matthew thought of an original

solution, a plan.

“You’ll have to store up,” he said.

“What? That’s crazy! I can’t take enough food for a year.” I dismissed his idea, as if it were a mosquito buzzing in my

ear.

“No, silly, store up like a bear,” he said. “ You’d better start eating now, so that when you are there,” he patted his

belly, “you will have plenty to get rid of.”

I rolled my eyes at the time, but, much to my surprise, his comments remained in my head. And during the last two

months before I left, while I was sending out change of address cards and trying to figure out how I would do my taxes

from so far away, I began to double my food intake. I had an extra slice of toast at breakfast and two bags of tortilla chips

at lunch. Soon people noticed my weight-gain diet and colleagues brought me chocolates for an afternoon snack, my sister

added an extra stick of butter to all the meals we ate. I suddenly became the one who got the last cookie, the extra shrimp,

the final piece of sushi or slice of pizza, and the thickest mound of cake. Even those who never, under any circumstances,

used to share their food would look at me, look at their food, look back at me again and say, “Would you like some?” But

no matter how many calories I consumed, I did not gain a pound or an inch.

I did, however, begin to wonder if the worriers knew something I didn’t. I mean, why did I want to go to a place

known for floods, poverty and diarrhea? Would I survive in a country where the water is poison and the food full of

chilies? I knew that Bangladeshi children often died of diarrhea -- could an American adult? But a plan was a plan. I had a

job. I had a ticket. I had a dream of travel. I had a new life to live. And despite the pained smiles of my friends and family,

I boarded the Dhaka-bound plane hoping I would be okay.

To my shock, I arrived in Bangladesh in the middle of Ramadan. Ramadan is the month of the Muslim calendar when

no one eats between dawn and dusk. The school cafeteria was closed. The tea stalls were closed. Food shops: closed.

Restaurants: closed. There was no prepared food anywhere. This was worse than anyone could have imagined. The second

day in Dhaka I panicked: before I could even get diarrhea, I was already starving.

On the third day I realized I had to cook for myself. I went to the market after work and looked at the vegetables:

potatoes and eggplants looked okay, I could peel them. But spinach, lettuce, parsley, tomatoes! My head began to spin:

could I eat things that I could not peel? Did I have to wash them with boiled water? I remembered reading in a travel guide

that I should add bleach to the water I clean vegetables with. Someone else said it did not matter, as long as they were

cooked. The thought of giving myself diarrhea from my own cooking was entirely too much. What would I do? I bought the

peelable vegetables and decided I had to ask someone for advice.

The next day at work a colleague told me she wasn’t sure about the vegetables, but she knew that some of the high-end

restaurants in my neighborhood were open at night. That evening I went to an Indian place near my apartment. The

restaurant was overly decorated in a raj style, on the 15th floor of a high-rise. Each table had a view of the congested

dusty streets below, but the traffic was far enough away that the only loud noise in the room was the air conditioning. I

ordered enough food for a small family, ate more than I should have, then packed the leftovers and was set for the next day.

For the next two weeks I discovered that Dhaka had more than its share of good food, if you were willing to pay for it.

Curries that dripped with oil. Naan slathered in butter. Thick daal and mango pickle. And there was a selection!

Indonesian, Thai, Indian, Bangladeshi, Italian, Chinese and Western. I wondered what my friends at home would think if

they saw how much good food I could get in Dhaka, Bangladesh. I laughed at myself for even thinking I had to go on a

pre-diarrhea-weight-loss/weight-gain diet. And in the first month -- no diarrhea, not once.

By the time Ramadan ended I discovered that most Bangladeshis of a certain socio-economic class don’t cook: they

hire someone else to do it. The thought of having my own cook made me so happy I could barely stop myself from hiring

the first person I interviewed. With my own cook I knew I would be safe. Eventually I found

Shiraj, and his food was marvelous: shrimp with fresh coconut curries, fried fish, pasta with a cauliflower cream sauce,

daal, rice, and curried vegetables. He made homemade pizza on Fridays and feta and tomato sandwiches that he carried to

my office for lunch. Not only could he cook, he could also learn new dishes. In time he was making humus, tofu with

vegetables, and banana bread. Banana bread in Dhaka, who would have guessed!

And as I learned more about the culture, I discovered that my Bangladeshi colleagues really liked to eat. Most days

when I looked up from my desk, someone was passing a plate of food around the office, and when they weren’t eating they

were talking about what they would like to eat next. I remember one morning I was greeted with a bag of Hershey’s

chocolates when I walked into work, and then after I ate my lunch I was presented with a plate of pad thai for dessert.

Food, food, food was the refrain I began to sing. I had never in my life had so much access to so much food. On a

normal day in Dhaka I was eating more than when I tried to overeat before I left the U.S., and most days I found myself

turning down food because I just could not eat any more. In time I did get diarrhea, a bout here and a bout there.

Once I was knocked out for a few days with diarrhea and a fever. But it wasn’t much worse than your average food

poisoning, and nothing my medicine couldn’t quickly cure.

After a few months of life in this new country, I found that those jeans that used to fit me just right, the size that I had

been wearing for over fifteen years, well, they didn’t fit so well anymore. They became a bit tight: six months in

Bangladesh and I put on six pounds. At that rate, I figured if I lived in Dhaka for a couple of years I would go home looking

like a curvaceous Bollywood film star. What would my friends and family say about that?

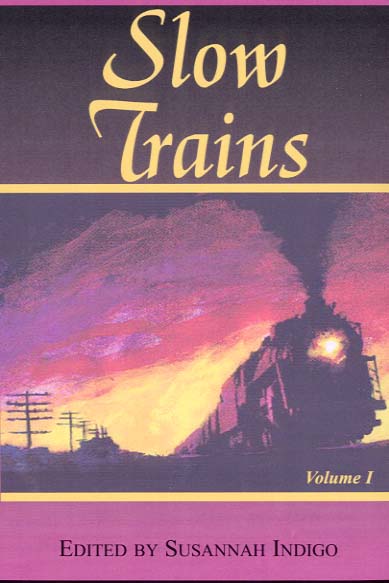

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print

Slow Trains, Volume 1 in print