Entering the Monastery:

An Ongoing Journal

(6/21/02 -- a new entry will be arriving from the monastery... soon!)

(Read Part 2)

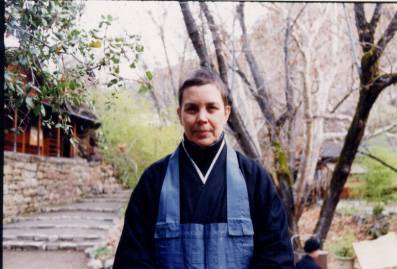

by Judy Bunce

Seven months ago I gave up a normal middle-class existence to become a fulltime monk at Tassajara, the mountain monastery of San Francisco Zen Center. I had done one practice period (a three month period of intensive meditation) here the year before, and left determined to do anything necessary to return.

Last November, I received permission from my teacher, Abbess Blanche Hartman, to begin the steps that lead to priest ordination. At that time, I asked the head of practice here what he thought the most important quality in a priest was, and his answer was "renunciation."

That's a word that I've been studying as I've moved through this, my third practice period. It's talking about the home, it's talking about the people, it's talking about the hair, it's talking about the stuff -- but it's talking about something even harder to give up: it's talking about my very sense of who I am. That's where renunciation lies, and that's what zen practice is about.

And so I'm going to give this entry a title:

Renunciation

January 2, 2002

Today my lifetime's accumulation of stuff went into a very funky storage unit in Hayward. Belongings in storage units are uninsurable, and it's an odd feeling to put everything I own into a little metal building, put a $15 padlock on the door, and drive away for five years. Very odd indeed. I think it will take some getting used to. My mind keeps turning back to everything lumped together in the darkness -- the couch, the art, the clothes -- getting used to their new situation, settling into a new configuration for a long snooze.

January 3, 2002

During my first Tassajara practice period, I had a profound experience of "no coming or going." As I was working up to being quite upset at having to leave, I understood that that was impossible. That I couldn't leave Tassajara, and Tassajara couldn't leave me. And that has indeed been the case. In the same way, I understand that I can't leave my teacher Blanche and she can't leave me. At our parting this morning, as she stays at City Center in San Francisco and I return to Tassajara, I told her that I didn't have words to thank her with, and could only thank her with my life.

January 9, 2002

I've mentioned the "shuso" a number of times, but probably haven't said that much about what it is. The shuso is the "head student," and there's one for each practice period. A shuso is someone who's been around for a long time and knows the forms thoroughly. They're usually a priest, and are assumed to have some knowledge/wisdom about the teachings. The shuso lives in the first cabin across the bridge from the zendo, a highly visible spot, and the cabin is small and unheated. The work of the shuso is always cleaning the toilets and tending the compost. It's an intense training position, and also a great honor.

Our last shuso, Marta, showed us what it means to be a monk/shuso, down to and including leaving the door to her cabin propped open all day, even in the coldest weather. Marta's originally from Colombia, and she's a rascal. But when she was shuso, she was totally straight-ahead good. She talked about it toward the end of the practice period, of the relief of being submerged in the role and letting go of "Marta."

The shuso for this practice period is one of the Green Gulch Farm people, one of those big easygoing guys who I like so much. He last lived here four years ago, and so of course I asked about his re-entry -- whether he, like I, quickly had the sense that he'd never left. He said the most striking thing was his realization of what a privilege it is to be here. It's common to gripe about the discomforts of living this way: as modern Americans, living without heat, without electricity, with two partially functioning phones for 60 people, can be nerve-wracking. I was glad to start with our new shuso on the flip side of that mind set.

January 14, 2002

Linda Ruth said "yes."

She was the last of the Abbotts whose permission I had to get before I could begin the next step in ordination. Since I knew she'd be down here to lead this practice period, I didn't try to get together with her over the interim.

I was the second person in to see her for dokusan after she arrived.

I started crying immediately. I've been doing this every time I see her, simply because she's not Blanche. First I got used to the abbott's cabin without Blanche's shoes outside the door, and now I have to get used to the abbott's cabin with other shoes outside the door. I really didn't want to cry in front of Linda Ruth, especially to start this discussion, but my tears are stronger than my willpower. So first we talked about missing Blanche, and about coming and going.

Then we talked about me, and why I want to ordain.

Linda Ruth's was the scariest of these discussions, because she emphasized the dangers I'll face after ordination. She talked about the way people, even our close friends, project things on us once we're "a priest." She said that we also become more sexually attractive to some people then, too, and the dangers this presents. I talked with her about the difficulties I've had in this area, calling sex my "achilles body." I told her, as I've told the others in these interviews, about the affair I had when I was back out in the world between my first and second practice periods. The way I like to tell it is -- The Buddha sat under the bodhi tree and Mara tried to distract him with sex and the Buddha said "no thanks"; I decided to come to Tassajara, Mara said "sex?" and I said "sure!" -- with disastrous consequences. Linda Ruth and I therefore talked about ordaining being too hard to do without help. When she asked whether I had any questions for her, at the end of our conversation, I said "Yes. Will you help me?" She said she would.

When I left the cabin, I thought service had started in the zendo because I could hear scores of voices chanting "All Buddhas ten directions three times" -- but they were still sitting zazen up there and it was totally quiet. It was my trickster friend the creek again, putting sounds in my ears that weren't really there.

My dear Ben is Linda Ruth's "Jisha," the person who accompanies her to and from the zendo and arranges her dokusan appointments. We wait to talk to her in the founder's hall, which is called the kaisando, a small building dedicated to Suzuki Roshi which is just about 20 feet away from the abbott's cabin. When I went back in the kaisando, because we wait there after dokusan until it's time to re-enter the zendo, Ben and another guy were sitting. When it was just the two of us, I leaned over and whispered to Ben, "She said yes." A couple of minutes later, when I was heading toward the zendo for lunch, Greg came running up -- on tiptoe because the paths are gravel and every step can be heard by the people sitting zazen -- whispered "Congratulations," and hugged me. In the 60 seconds between my telling Ben and walking toward the zendo, the news had begun to spread. I returned the hug and whispered "Will you help me?" "Until the day we die" was his answer.

But up by the zendo, waiting for the bell to ring to enter, I felt scared by what Linda Ruth had said. Can I really do this? Is it really what I want? Then I thought of Marta talking about the relief in being "the shuso" instead of "Marta," and I remembered that being less of This and more of That is what I came here for. So yes I want it, and with help I can do it.

January 16, 2002

First, the weather report. It's cold! The mornings have been in the low to mid-20s for the last few days, and last night was the first time I woke up and thought I needed another blanket. Right now it's 9:30 in the morning and the thermometer says it's 53 degrees here in my fancy insulated room. I'm sitting right by the fire, which has been burning since about 7:30, and all three kerosene lamps are burning. I'm wearing heavyweight thermal underwear, flannel lined pants, a heavy wool sweater and a hat. I have on cashmere socks under polartec 300 socks, and my feet are still like blocks of ice. It's cold!

So here's what happened on the job thing.

During tangaryo week, when we were all doing general labor, I spent two days hauling old blackberry vines to a burn pile down in the flats. My partner was a 21 year old girl. I of course kept up with her, and even enjoyed it. But this screwed up my back again. So I told the work leader I needed a non-physical job, and she put me in the library for a couple of days.

The library. Warm. Quiet. Full of books. Yes.

While I was waiting to find out who was going to take the sixth doan postion, hoping desperately it would be me so I could be a big cheese in the zendo, I mentioned to one of the seniors that I wouldn't mind being librarian. It's always been a part-time job, and I figured I could work it in. Besides I surely wanted it to look like I didn't care about any big fancy jobs.

The morning after the Abbess arrived, we had the opening ceremony and the jobs were anounced. I'm the librarian, nothing more and nothing less. Now I putter around on my own, getting familiar with the stock, even sometimes lying down in a patch of sun to read a book, finding miscategorized books and getting them where they belong, thinking how the place can be improved (a section on sex and spirituality! a section on work and spirituality! a section of spiritual biographies, which I happen to love!). People know where to find me during work period and stop by to say hey. This is a good job.

January 20, 2002

Wendy Johnson, the longtime head gardener at Green Gulch, is here for a month and has been coming into the library to write in the afternoons. After letting her get some work done, at the very end of work period, I asked her my question this way: "We all come here to study the Buddha dharma, and yet once we're here we spend a lot of our time and energy on getting along with other people. Does that mean that getting along with other people is the Buddha dharma?" Wendy said yes, just as I thought she would, and she reminded me that there is nothing that's not Buddha dharma. I saw the fallacy in my thinking, in creating a universe where this qualified but this didn't.

What a disappointment!

I wish that there really were a monastery I could go to where all we did was swan around in beautiful black robes and everything was peace and love all the time. I don't know, maybe that really is the monastery I got, it's just hard to see it sometimes.

February 4, 2002

It snowed for 36 hours! Fantastic! I was a server the first morning. We put the pots of food on tables set on the porch behind the zendo, and bring them in at the signal. There's always lots of standing still, hugging ourselves and shifting from foot to foot in the cold outside air. That morning there was standing and staring at the landscape as the snow fell. The minute the last serving chore was finished, I ran to my room and got my camera and shot off a roll of film. I even got some shots of the Abbess building a snowman with the children.

It snowed for 36 hours! Fantastic! I was a server the first morning. We put the pots of food on tables set on the porch behind the zendo, and bring them in at the signal. There's always lots of standing still, hugging ourselves and shifting from foot to foot in the cold outside air. That morning there was standing and staring at the landscape as the snow fell. The minute the last serving chore was finished, I ran to my room and got my camera and shot off a roll of film. I even got some shots of the Abbess building a snowman with the children.

Having the little kids here is such a blessing. There are two young families participating in this practice period, sharing child care and zendo time. The little girl, Olivia, is 2-1/2; the little boy, Lucas, is a little less than a year older. I found myself in their vicinity with bubble soap in my pocket one day, and we all learned together that if I blew bubbles, the Tassajara puppy would jump for them. Now I have little bottles of bubble soap in all my jacket pockets. One night I was coming down from serving dinner, rushing through the dark, in my robes, hat pulled down to my eyebrows, and Olivia, riding past on her father's shoulder, called out, "The Bubble Lady!" Amazing. Last night she topped that. I happened to be heading in the same direction as Olivia and her mother and walked alongside them. Olivia was crying: she'd fallen in the dining room and hurt herself. I said some words to her as the three of us walked together, she continued to cry, and then she said something through her tears. Her mother translated: it was "How's your owie?" I scalded my hand filling my hot water bottle a few days ago and got a spectacular burn. The hand has been wrapped in gauze and is just now recovering. This little baby found a moment in her own pain to reach out to me and ask about mine. I think this must be what good parenting brings.

I've been waiting and waiting for my okesa fabric so I could start the long process of sewing that leads to ordination, and finally gave up and cut myself a black rakusu during the last sewing class. The okesa is the large rectangle that gets draped over our robes, and it takes months to make. The rakusu is the simpler bib-like rectangle that lay people wear in blue and priests wear in black when they're not wearing their okesa. Priests' are usually sewn last, or sewn by members of the sangha, but I went ahead and started mine because I so feel the need to do something. After I'd marked the black fabric, coming at it with scissors was quite a moment. Having started, there's no stopping, no unfinished rakusus or okesas, no room for second thoughts. I bowed to the fabric, blinked my eyes to clear the tears, and cut.

Now we're starting a nine day sesshin. Straight on through, no talking or reading, short rest periods, and zazen zazen zazen. Okay. Gotta go get ready.

February 14, 2002

End of the nine day sesshin.

Whew.

A burned hand doesn't hurt so much at the time of the accident, but the

recovery is grueling. I sat with considerable pain while the poor thing went

through its changes. I had dokusan on about the third day of sesshin. First

I told Linda Ruth that I was having trouble breathing, that I felt like I was

strangling. I told her that I thought that we'd put the snake in the tube (a

common expression of what we're doing here, though I still don't know why we

want straight snakes) and then stuffed an okesa in too, and there wasn't

enough room for it to breathe. We talked about that. And then we talked

about my hand. I told her that I kept thinking "My pretty hand! All

scarred!" She replied that someone had once said to her, when she was having

similar thoughts, "What do you want to do, have a good complexion, or be a zen

master."

I want to be a zen master.

February 22, 2002

The loneliness has really been getting to me. We're all sleep-deprived and

irritable and sick to death of being cold, and I'm trying to find the line

between being kind to others and taking care of myself, and failing, failing,

failing. The romantic bubble I built around someone sitting across the zendo

from me has burst, and it's come home to me that I'm here to study

Buddha dharma and not to find romance. And that I really do have to choose

between those two, at least as long as I'm in priest training and committed

to remaining here at Tassajara.

Today I spent the second period of zazen with my head in the crook of my

elbow crying. When the robe chant came, I didn't put on my rakusu. When the

bell rang for service, I quickly walked out of the zendo.

I went into the kitchen for sick food about half an hour later, and talked

with the day's breakfast cook. She said "Are you sick?" I said "Mentally."

She said "A lot of people are feeling that way." We talked about Blanche,

and a lightbulb came on over my head. I ran to the phone in the stone

office. Since everyone was still in the zendo having breakfast, the phone

was free and I could have some privacy.

Blanche answered. She pop psyched me a little -- she knows me so well -- on the

loneliness question, and when I cried, "This is too hard, I don't think I'm

strong enough to do it," she answered, "You are, you are." I was placated, but

not satisfied. I roamed around a bit -- the student body was now out of the

zendo and on their break -- and a couple of women, the ones who'd heard the sounds

of sniffling and nose-blowing and paid attention when I exited, whispered

encouraging words in my direction. One suggested going back to bed and

getting some sleep. But that wasn't what I needed. A walk, I thought. So I

set out toward the flats.

But instead of going straight by the bathhouse, I hung a sharp right at the

small sign that says "Path" and went up to the Suzuki roshi memorial. It's a

sharp climb on a narrow dirt trail, with a gentle nearly-straight stretch

just before the final bend. It was on that stretch that I started calling to

him. "Suzuki roshi, help me. Suzuki roshi, it's me, it's too hard, I can't

do it. Suzuki roshi I'm lonely." I walked in circles in the clearing in

front of his memorial as I talked. Finally I knelt down -- no, it was more of

a crouch than a kneel, I was still doing none of the forms, no bows, no

rakusus, no incense, no chants -- and put my head on the rock that serves as

his altar. Before I did, I noticed that one branch above the large rock that

stands in tribute to our founder was gently nodding up and down. I checked:

it was the only branch in the clearing that was moving.

"It's all zazen" is what entered my head. "Nothing is excluded from zazen.

This right here, kneeling in the dirt and crying, this is zazen. Zazen is

much, much bigger than you can imagine, and it's all there is for you to do.

Come back to this moment. You don't have to worry about being a priest, being

poor, having or not having romantic attachments. Just relax into the zazen

of this moment and let the other stuff go."

Thank you Suzuki roshi.

The rest of the morning continued strange, almost dreamlike. My boys came to

my side with their own brand of helpfulness: Greg asked how my burn was

doing ("How's your owie?" he whispered), and Ben asked whether I still had a

good supply of the jasmine tea I like so much. Mostly I felt protected from

likes and dislikes, from abundance and lack, by the immense bubble of zazen

that included it all.

February 28, 2002

I talked to Blanche yesterday, quite by accident. When we got to the part

where I whispered into the telephone about going up to the Suzuki roshi

memorial and receiving his help, she boomed out, "Did he talk to you?" When I

said yes, she again boomed, "Lou (her husband) does that all the time!" Oh.

Maybe it's just that easy.

Yesterday was a workday, and we always have dining room lunch on workdays --

leftover soups, some starch, some salad, either leftover or fresh. I got my

food and went out to the lawn in front of the stone office and ate on the

grass with a group of people. The families were over on the other end of the

lawn, and the kids ran back and forth between the groups, begging bites of

cake and dodging the boys playing hacky sack. There are clumps of daffodils

everywhere, and we were sitting under an old tree that was covered with

sweet-smelling white flowers. People began to move away, and eventually Greg

and I were left alone, leaning against the old stone wall, watching our

friends playing. "Oh yes," I said to him, "This is certainly hell."

March 1, 2002

I went out to the chiropractor yesterday -- a whole minibus full of us went.

Kosho drove, but all the rest of us were women. I said we should have a sign

for the side of the Suburban saying "Transport for the Institutionalized

Mentally Ill," because that's probably what we looked like. When I

called out, "Do we have to go back so soon, Dr. Kosho?" in front of the

Monterey Whole Foods, he didn't think it was funny. But the point I have

to make is, the world looked just awful. We were at Del Monte shopping

center, which is one of those upscale places that people work all their lives

to be able to shop at, and it looked like the living dead driving Porsches

and Mercedes to me. It was really a shock. I'd become bored and restless

here in the valley, but my excursion (we hit two or three other shopping

centers in our relentless search for stuff) made me very, very grateful to

be here

March 7, 2002

In between the two chunks of time we spend in the zendo in the morning, we

have a one hour "study hall." It's become one of my favorite parts of the

day.

Study hall takes place in the dining room, and we're asked to read Buddhist

books, but we're also allowed to sew sacred things. At first I read

"Branching Streams Flow in the Darkness," Suzuki roshi's lectures on the

Sandokai, then I listened to tapes of Reb Anderson's famous sesshin where he

lectured on sex, and now I'm sewing on my okesa.

There are two parts to the dining room: the front part, which is where

everyone sits because it's heated, and the back part, which is where a few of

us sit because it has lots of elbow room. It also has sun streaming in the

windows at this time of year, and sometimes I get in the downdraft from the

stick of incense that the servers have left burning, and I look up from

whatever I'm doing and utter a little sigh of gratitude at how beautiful it

is. The windows look east toward the back of some dumpy little cabins; at a

huge rock which is covered with moss; at lots of trees; and at the creek.

While I was listening to Reb's tapes, I stationed myself at the window and

gazed and gazed and gazed. But now I sit at a special sewing table that's

kept clean and has two lamps for the sewers to use.

There are two parts to the dining room: the front part, which is where

everyone sits because it's heated, and the back part, which is where a few of

us sit because it has lots of elbow room. It also has sun streaming in the

windows at this time of year, and sometimes I get in the downdraft from the

stick of incense that the servers have left burning, and I look up from

whatever I'm doing and utter a little sigh of gratitude at how beautiful it

is. The windows look east toward the back of some dumpy little cabins; at a

huge rock which is covered with moss; at lots of trees; and at the creek.

While I was listening to Reb's tapes, I stationed myself at the window and

gazed and gazed and gazed. But now I sit at a special sewing table that's

kept clean and has two lamps for the sewers to use.

The okesa joke is that we take a perfectly good piece of cloth, cut it up,

and sew it back together again. Okesas were originally made from fabric

found in the charnel grounds, but that was a long time ago. Now they're made

from the nicest cotton we can afford. Blanche found me a cotton that's so

fine it feels like silk. Since this is zen, our basic okesas are black. It

will be a rectangle with seven panels, and I'll wear it over one shoulder,

wrapped around my body over my priest's robe. It's all sewn by hand, with

tiny little stitches that appear like dots. I'm sewing with a medium gray

thread, so the stitch is evident but it doesn't shout for attention. Every

time we put the needle into the fabric we say "Namu," every time we pierce

the fabric in the next spot we say "Kie," and when we pull it through we say

"Butsu." Which means "I take refuge in Buddha." This is said, of course,

only in our minds, since we sew in silence. I'll take thousands of these

stitches and take that refuge thousands of times before the garment is

finished. Some of the sewing has to do with how you work the needle, but at

least as much has to do with how you hold and move the fabric the needle's

going into. My left hand -- my holding hand -- has a fresh big angry red scar

from my accident with the scalding water, and working with the fabric right

under the light gives it such prominence. It's quite a contrast between the

beauty of the garment and the scar on the hand holding it. Sometimes I stop

sewing and look at it closely, and I think of Linda Ruth's "Do you want a

good complexion, or do you want to be a zen master?" I still want to be a

zen master.

Yesterday was rainy and warm (probably around 50 degrees). Greg sat across the

sewing table from me, working on the ties that will hold his okesa together.

He's nearly finished sewing, and his ordination is on April 20th. I was

putting the short seams in my second of seven panels. Myo was sitting at

another table off to my left. Sonja, the head of housekeeping, was sitting

behind me, laughing quietly at whatever she was reading. Julia, a tangaryo

student, was over by the window, head on the table, softly snoring. The

puppy came rushing into the room, tired and bored from being cooped up in the

rain. He's about ten months old now, and it looks like he's going to work

out. Last September I was predicting otherwise, but Sonja took him in hand

and got him trained and he's settling in. But yesterday morning he was

anything but settled, hopping around the room with his chew toys, looking

for a pal. Myo, of all people, our elegant and strict practice leader,

grabbed the end of the toy and pulled it and the dog back and forth. The

rest of us looked up from what we were doing, smiled, and then went back to

our work. This is sangha.

I've been given permission to step outside the schedule and call Blanche

during breakfast once a week. With two phones, one of which is often broken,

for 61 people, calling her while everyone else is stuck in the zendo is the

only way I can be sure of being able to call, with the bonus that I'll have a

bit of privacy. It's a good time for her, too, between service and breakfast

at City Center. I had to get the permission of the practice committee, and I

like to imagine someone saying, "Yeah, let her do it, maybe it will calm her

down a little," since it's unusual to be allowed to break ranks with the

group, but who knows. It was sweet talking to her this week. We talk a

little about her (she just had a cataract removed from one eye), a little

about me ("Ordaining just makes you a bigger screen for people to project on

to"), and a little about sangha members both here and there. I'm very lucky

indeed to have such a relationship with such a woman.

People are starting to talk about the summer, about where we'll be living and

what our new jobs will be when Tassajara changes from a strict monastery to a

resort for rich people run by zen students, and I'm not taking it very well.

I'm so pleased with things as they are, I don't at all want to rush into

changing them. Yesterday I went down to the barns, which is where students

live in the summer. They're not used for housing during practice periods,

when we live in the rooms that our rich guests occupy during the summer. If

I get my choice (and I probably will), between April and September I'll be

living in a roughly finished room about 7' by 10' with a screened window

facing the creek. I'm going to ask if I can keep looking after the library,

but that's not a full-time job during the summer, so I'm also going to ask if

I can work in the office. But that's nearly a month away, and now, at 7:15

at night, it's 45 degrees outside and I have a cozy fire burning in my wood stove in

my large luxurious room while I write to you.

March 10, 2002

I did my taxes yesterday. It looks like Uncle Sam is going to give me the

big lesson in renunciation. The government is going to take the final

pittance I still have in the bank -- my escape money, my rainy day money, and

my money I'll need if I have a health problem -- and I'm going to have to find

a way to live on my stipend of $150 a month. I'm going to be, at age 58,

back to zero. This was a shock to me. I knew I'd owe money, but not this

much. I could leave Tassajara to make more money, but if I did, I don't know

whether I'd ever get back. This is too important. I have to do this, and I

have to do it now.

March 12, 2002

Continued signs of spring abound at Tassajara.

The gardeners stuck a bunch of willow sticks in the ground down by the baths,

part of a project to suck the soap out of the water from the bathhouse before

it returns to the creek. A few days ago I noticed that those twigs had signs

of life, and yesterday those signs of life turned into little green leaves.

What an agreeable tree the willow is!

The gardeners stuck a bunch of willow sticks in the ground down by the baths,

part of a project to suck the soap out of the water from the bathhouse before

it returns to the creek. A few days ago I noticed that those twigs had signs

of life, and yesterday those signs of life turned into little green leaves.

What an agreeable tree the willow is!

Once I was inside the bathhouse, one of the women was pointing and gesturing,

making her hand go "quack quack quack." In silence, dripping water from the

showers, five or six of us moved over to the wall of windows to see the two

migrating ducks that were swimming on the creek.

After we eat a meal in the zendo, we all stand at our places while the priest

leads us through three bows and then gracefully exits through the door that's

been opened for them. Last night after dinner, a little bat flew in the open

dor and swooped and glided around the zendo. I actually managed to bow once

just as he was heading toward my corner, but there was nothing I could do to

disguise my instinctive fear when he came at me again while we were filing

out. There were grins on many faces and I was smiling too, at the same time

as I was cowering. I'm not afraid of the bat, just of the unpleasantness of

having him come too close and get caught in my 3/8" long hair.

Best of all, during zazen last night the frogs started croaking. Tassajara

is built along Tassajara creek, and it's intersected by Cabarga Creek.

Cabarga has been flowing since the heavy rains started, and it's nearly dried

up now. That's where the sounds came from; there must have been tadpoles

waiting in the mud for the mud to warm up. If the frogs are back, can the

crickets, and summer, be far behind?

March 19, 2002

I have to be here.

It's not just that I don't want to be there, it's that I have to be here.

Just as I can't turn Judy into "a priest," but am going to have to stretch

"priest" to include "me."

Neither being here nor ordaining is a turning from. They're both a turning

to.

And if my finances are such that I'm even more thoroughly dependent on the

triple treasure of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha to take care of me -- good. If

pinning my hopes on romance with someone led to heartbreak -- good. Because

there's no point in doing a thing like this if there's any holding back at

all. And I am so doing a thing like this.

I still want to be a zen master.

To be continued in the next issue of Slow Trains...

©2002 by Judy Bunce

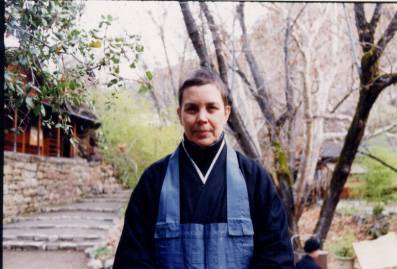

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.

Judy Bunce is a zen monk currently living at Tassajara Zen

Mountain Center, the training monastery of San Francisco Zen Center.