Anna takes my hand and slides it inside her pajamas, down between her thighs, and my fingers dip into warm wetness. “It’s just an idea,” she says.

Five minutes later, Anna’s hands are splayed up against the kitchen counter. Her pajamas are on the microwave. The taste of her is in my mouth, we’re tangled up, her pale legs around my brown hips, my hands holding her up and the moment I’m inside her—fully inside her, every part of me slick and hummed with feeling—it occurs to me that this is the first moment of completely unprotected sex I’ve ever had in my life.

And then she lets out a low moan and we start to rock together, half-standing and urgent, and the thought slips away.

“You are so hungry,” she murmurs. “My wolf.”

It’s a problem of the English language, which I learned when I was five,

but still. The thought rises up, surprises me. It floats above our bodies.

In calling it unprotected sex, unsafe

sex, those dangers taste pretty fucking delicious. A condom holds me from her, defends us against each other. The word guards us from babymaking and it beats back death. Unsafe sex assumes I need to be saved.

I’ve been dating Anna for five months. We met salsa dancing in East LA,

in one of those movie moments: crowd parts and there she is, this beautiful geek,

except unlike the movies she’s holding a sombrero margarita glass. She’s a good

dancer for a white girl—it’s all in the hips. During the day, Anna’s an epidemiologist, which means that in between moments when we’re having the best sex of my life, she’s citing statistics and studies and odds about sexually transmitted diseases. In those times when I’m reminded that I’m going to die, my mouth is pulled to her throat, which I bite lightly, and she laughs and I breathe her in. She smells like ache. It’s a brilliant laugh.

A week ago, Anna’s at the computer. She’s entering data in a calendar program, sipping her coffee. Her cats only barely open their eyes when I walk into the living room. I’ve got the element of surprise in my favor; I move on the balls of my feet, one foot then the next, but the floor creaks and she’s on to me.

“Hey,” she grins. “I have a proposition you’re going to love.”

“Yeah?” I slide my hands over her shoulders, finger her collarbone. Yesterday’s entry in the software program shows body temperature, a red circle and a red heart. Anna stretches up and kisses me, and I want her and my morning coffee in the same moment.

“Now don’t react until I’m done speaking,” she says. “I’ve been tracking my fertility for the past three months. With this software,”—and here she grabs my neck because I flinch—“I can predict exactly when it is most safe for you to come inside me. When it is medically nearly impossible for us to conceive.”

Nearly. My girlfriend the scientist is using fertility software as a contraceptive device.

“I don’t want kids yet,” I say. We just started dating, I don’t say.

She stands up and goes into the kitchen. “Neither do I. But I’m not going back on the pill at 30. Just… as an occasional treat. No latex, no UTIs, no yeast infections. Just you and me.”

Then she pulls my hand down to touch her, and we’re up on her Mexican-tiled kitchen countertop, and it’s like I said. I lose my mind for a second.

At work I can’t think about anything else. We have a window of seven days in the month where we’re in the clear, and we’ve just spent my lunch break in the back seat of my car in her company parking lot, fiercely fucking. I can still feel her around me.

It’s the seventh and last day today. I think everyone around me in the office can smell the sex we’ve had when I get up to use the photocopier. I feel like I’m getting away with something; I know exactly how at risk I am, but I can’t quite care as much as I should. I’m thirty years old and doing things I would’ve slapped myself for at sixteen.

Last night I catch myself saying what if, what if we might have a baby because of this thrust right here. Or this one. Or this one. And Anna moves faster, and I feel a flood and simultaneous tightening. It’s not the idea of pushing a child through her

anatomía that’s getting us off, followed shortly by raising and educating that offspring for the next two decades. No, we’re children of divorced Catholics; we’re terrified of raising a kid, baffled by that kind of commitment. It’s the notion of making a kid that’s hot somehow. Conception and creation, very sacred. It also makes no sense.

I’m thinking about this when Fat Tuesday ambles into my cubicle. She says,

“Check this shit out, BP,” and then she pushes up her big black blouse to reveal the ever-expanding tattoo on her back. My name’s Jorge, but Blanco Paco’s her name for me. She claims I’m the whitest Latino she knows.

Let’s be clear: with her shirt on, Fat Tuesday is not beautiful. She’s a big girl who moonlights as our receptionist, but her main expertise is instant messaging and trash talk. She’s definitely not what you expect when you walk into an H&R Block, but there she is. Tuesday wears silver hoop earrings bigger than a fist. Her lips are lined with a dark brown pencil. She likes to look sly. Her ex-husband is a tattoo artist up in Carpenteria. Every time she gets a paycheck, she comes back with more of her back fleshed out: cobalt waves and white wisps, green currents, blood-orange coi emerging from the depths of her, riding up over each fat fold of Tuesday’s back. Golden scales rimmed with amber.

Every time he fills in some more of the mural, her ex-husband refuses money.

Just a little sugar, he asks. Tuesday, apparently, gives the best blow jobs ever,

but she insists on paying him instead. “I wouldn’t even be his whore when he

begged me to,” she says.

I know all this because she can’t seem to help confessing to me.

Especially when I’m in-between clients, my arms full of 1040s and IRS folders,

she hikes up her shirt in my cube and says, “Look...I got more done this weekend.”

And I have to admit, every time the lines fill in and blossom with color,

I’m impressed. I’m not sure how she’s able to apply moisturizing lotion back there,

over each rounded hill. Fat Tuesday could be the daughter of one of those women

in the Central Valley who pick strawberries from dawn until dusk;

she doesn’t get tired easily. But Tuesday is Chicana by way of New Orleans,

whatever that means, and to hear her tell it, there’s a lot I don’t know re:

what men really like.

“BP,” she says, “this is a second-rate tax shop.” And it’s true, I don’t know much more than Turbotax. But I speak Spanish and English and I smile if you’re not a total dick, so. I like walking through the lives of people, seeing them year after year. What you spend and how you spend it says a hell of a lot about who you are right now—as opposed to who you want to be. Fat Tuesday is sitting in the nice chair in my cube reserved for clients, scrolling through her phone. Truth is, Tuesday bucks the trend, since who she is today is exactly who she wants to be a decade from now.

“Damn. My tat itches.” She’s rubbing her back irritably against the chair. I want her to go away so I can get my work done early today and get back to simultaneously worrying and replaying the lunchtime incident in my head.

Instead, the words just jump from my mouth. “Tuesday, you ever get nervous about disease? When your husband tattoos you?”

“Ex-husband. And hell yes. The man’s a skank. I watch him unwrap the needles every time. He sterilizes everything when I’m around, but who knows when I’m not, right? He’s a master craftsman, but he’s still a dog.” She sits up and looks at me closely for the first time today. “BP, you look different. You been running or some shit? You look

good.”

When I get to Anna’s house, we do ordinary things. We make pasta, I wash the dishes. She teases me about the Dodgers, who can’t seem to make a hit for the third game in a row. I point out that the paper said that bird flu was discovered in Korea today, so it’s shaping up to be a good year for disease. Virus 10, Humans 0.

She laughs softly, shakes her head. “We’re too cynical to have kids if we always cheer for the disease.”

“And we’re too poor,” I say. I’m up to my arms in soap suds, working on a pot with penne welded to the pan.

“I don’t know about that. Anyway, we’re back to the condoms tonight, so it’s nothing we have to worry about for another month at least.” She slides her hands in around mine in the hot water, then buries her head in my shoulder. The pasta won’t come off no matter how hard I scrub.

“You’re such a nice guy,” she says.

It feels like love and condescension at the same time. The kind of thing you say to a guy who graduated from Cal State LA in accounting, a guy who tries real hard.

“Nah, that’s someone else,” I say. “Nice guys don’t fuck you in the parking lot.”

She doesn’t lift her head. “Uh huh.”

Later that night, we’re half-naked on the couch as the baseball game winds uselessly down to the 8th inning. Anna is a night-blooming flower; my lungs begin to expand with the stealthy smell of her, low and sweetly metallic. My mouth wanders to her hipbones, to her thick lips which are almost violet. When I tongue her, searching, she’s already wet with a thick, sprung honey, and her hands grab my hair and pull me down. I keep drinking her in, even when she demands I grab a condom, her legs tense and shiver, she pulls at my hair and faster than I expect her clit swells, pulses and she explodes into my mouth, a flood of sound in the air.

I climb up and watch the color flow from her face as she grins.

“Hey,” she breathes, looking up at the ceiling. Then, eyebrow arched: “That is some kind of self-control, choosing to not fuck me.”

All that wetness so close to my cock, which hums hot against her thigh.

She closes her eyes and says smiling, “You’re such a good wolf.”

And then it happens fast. My elbows settle and my hips thrust forward and my head swells full and I watch her eyes open wide, shocked. I’m the dog taking meat from the table, I’m the child with chocolate around his mouth, I’m deliriously fucking guilty and I do not want to stop.

With a deep moan and a shout, she places her hands on my chest. “Jorge!”

And then I pull out, just before. Just before.

“What were you thinking?” she asks.

“I wasn’t,” I reply. “I just...wasn’t. It didn’t feel real.”

She sits up in bed. “You pinned me down.”

“Did you like it a little?”

She sighs. “I don’t know. Maybe. Maybe we shouldn’t have stopped using condoms.”

I try not to say it, but it comes out anyway. “I don’t know if I can ever go back to using them.”

Anna turns on the light. “What?”

“I mean, of course I can, but...this feels so alive.”

She gets up to go to the bathroom. “We are so going to get pregnant. Jesus Christ.”

My generation, we’re addicted to safety. We came up in the first wave of safe sex. At

thirteen, I saw so many commercials about HIV that death and sex seemed like the

same thing, guaranteed in the same instant you yielded to what felt good. And growing

up in a tough part of town, lots of folks have little kids early. My uncle, my

older brother, my younger brother. Those guys are stuck, man, they can

never leave the Heights—which at seventeen, from the outside, looks like

the same fate as getting sick.

When Magic said he had AIDS, we all talked about it after scrimmage; of course he did.

If I played for the Lakers...well sure. It was like tempting the gods if you were famous. And if you were ordinary, like us, you might escape a thunderbolt or two, but not for long. We were all going to get HIV, it was a matter of time. It was everywhere, AIDS was all we heard about—even if I’d only known one person who actually died, and he was one of the priests who taught at the high school.

My father sat me down once, at the end of our big and only sex chat, and told me even good girls get diseases. He even managed to look sad when he said it. That’s a hard image to shake when you’re sixteen and going down on Cindy, who is definitely not a good girl.

And that’s the thing. How do you stop being excited by risk once you’ve tasted it?

Condoms dull, they blunt. It’s not that you don’t feel anything; it’s that you

know what you’re not feeling. What couple hasn’t teased around the edge, the lips, imagined what it would be to fuck and avoid consequence? Your body knows it deep down, it’s all tones and shades of slippery, it’s subtle and darkly wet instead of a straightforward path, you swallowing him up, all the rounded slick turns, the thousand places where she squeezes you and he strokes up along her and your bodies fit together as if they were always meant to.

Except there’s no way to avoid consequence for long. The thunderbolt, it’s coming.

The next day at work, Tuesday and I get lunch at Taco Lita around the corner. The table’s outside, a feeble ring of tiles on a slab smeared with hot sauce. I tell her about the previous night and Fat Tuesday laughs.

“Why’s she freaking out? Don’t your girl know about pheromones?”

“What?” I’m busy flicking lettuce into the parking lot.

“She’s ovulating, right?”

“Well, yeah. That’s the problem.”

“And you gotta have her. There you go. Simple.”

“Right. Like all Mexicans got to have lots of kids.” I rub my eyes. “Really fucking enlightened.”

“We’re animals, Blanco Paco. White, brown, whatever, goes past reason. Chemicals coming from her pores make you want to have a baby.”

Fat Tuesday leans forward across the table, and in order to look away from her cleavage, I get a clear shot straight down the back of her shirt. She’s a rippling aquarium drenched with color. Tuesday grins. “Women got some serious power in their sweat.”

“Sometimes I think I’m not even her type,” I say. “You know? She needs a professor or a blue-eyed banker or… something.”

“Listen to me, BP. Listen. You both are trying like hell to make a baby. Doesn’t matter what you think she wants. You’re being what you need to be. So’s she.” Tuesday grabs my taco and shakes her head. “Just own it, you fuckin’ pussy.”

It’s been a week since we’ve seen each other. Anna invites me over for dinner. I, of course, bring flowers because if she’s already pregnant than at least she can say to our son that I brought her lilies when she told me.

When I get there, the lights are out. The back door’s open, so after knocking I walk in and lock it behind me. She’s in the bedroom, wearing a robe. Anna laughs nervously and points to one of her chairs from the kitchen.

“Sit, wolf.” I do.

She pulls my arms behind my back, then binds my left wrist to my right with rope. Where did she get rope, I think, and how did she learn how to tie knots like that? She grins and produces a black kerchief, blindfolding me firmly. And then she kisses me long and deep. I don’t know where she is.

I feel her before I understand what I’m touching: the fingers tied behind me slide along the edge of warm, wet folds. My belt buckle goes, my pants are undone, yanked around my ankles and left there.

“My shoes are still on, m’ija.” There’s no reply, and in truth, I’m throbbing.

And then all of my senses focus on the proximity of Anna, inches away from my chest,

my mouth—her hair, her skin, her sweat, her legs straddling my legs, and she teases

me in slow strokes with her hand. The juice of her dripping down, coating her fingers

as they grip slippery and push slowly, achingly down over the head of

la riata.

I can feel the heat of her pussy not even an inch over me, and as my hips arch up

to reach her she uses two wet hands to encircle, stroke, hold me down by the shaft.

I know this without sight, I know where she must be as I thrust up toward her, but

every time I’m held tightly with a squeeze and kept at bay. I can’t see her,

but I know her. Anna’s long throat, Anna’s caramel eyes, Anna’s favorite way to

walk to work. Anna’s fears of dying alone. The roughness of her knuckles, the

abandon with which she loves her job, the way she was gracious and funny when

my mother burned dinner when they met a month ago and Mamá trying not to cry.

The way she looks at me before we fall asleep: not possessive, not wary,

not distant. No barriers, no safe space. Just her looking into me.

She takes off my blindfold and she says, “I want to see your eyes,” as she lowers herself onto me. We start to sway, both of us, in long slow strokes, and I feel Anna filling every part of me.

“Should I stop?” she breathes. “Do you want me to stop?”

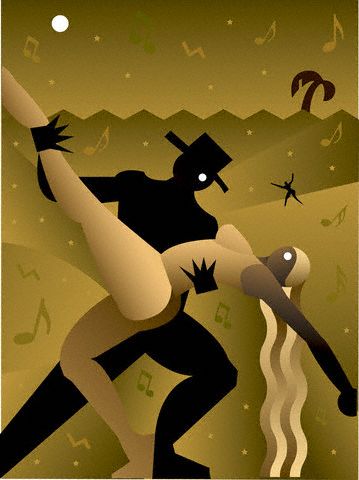

And for an instant, Fat Tuesday flashes through my head, the magnificently frank abundance of her back, and as I start to get closer and closer, the light goes golden, all brilliant gold, golden scales rimmed with amber.

“I want you,” I say. And I do.

©2007 by Ryan Sloan

Ryan Sloan grew up in Los Angeles and teaches writing in the Bay Area.

A recent graduate of New York University's MFA program, Ryan's work

has appeared in L.A. Weekly, Opium Magazine, The Modern Spectator,

Locus Novus, Poor Mojo's Almanack, and Painted Bride Quarterly.

He's at work on his first novel.

"The Opposite of Animal" was originally published in Nerve Magazine.